20th March 2024

Thank you, Mr. Bush , December 2019

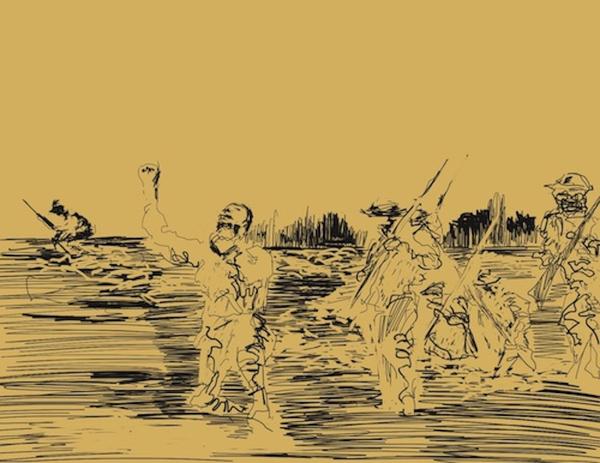

Thank you, Mr. Bush, for Invading our homeland,

Thank you, Mr. Bush, for Turning Iraq overnight into a battlefield with illusive borders

Thank you, Mr. Bush, for Disbanding the Iraqi Army, founded in 1924

Thank you, Mr. Bush, for Inciting a sectarian rift, leading to a civil war for years to come.

Thank you, Mr. Bush, for Sixteen long bloody years making Wadi al-Salam in Nejaf the biggest

cemetery in the world